An idea that has been floating around planning circles for a long time is the concept of “Regionalization.” Put simply, that land use and governance should be administered regionally as opposed to being administered at the municipal or County level. There have been nods towards regional governance, but no full adoptees. Many populated areas have a Municipal Planning Organization (MPO) which oversees federal transportation dollars, a regional park/trail system, and often a Council of Governments exists to “coordinate action” amongst jurisdictions. We acknowledge that there is an interwoven connection between jurisdictions within a region but then return to our silos, leading to land uses which do not foster the diverse, dynamic communities we aspire to. As Karen Chapple puts it, “To plan for equitable and sustainable regions, we need to start from an understanding of how regional economies, economic opportunity, and family lives work today in each region around the world, and then link that to growth management planning.”[1]

Others have written more eloquently on the subject, but I will quickly go over what I believe to be the best arguments for Regional Planning.

Shared Revenue – Coordination as Opposed to Competition

The cornerstone of a regional approach is the sharing of revenue, the most famous being Minneapolis’ tax base sharing agreement (known as the Fiscal Disparities Program)[2]. By sharing a portion of revenue amongst jurisdictions to reduce fiscal disparities, it allows jurisdictions to worry less about scrimping and scrapping for funds.

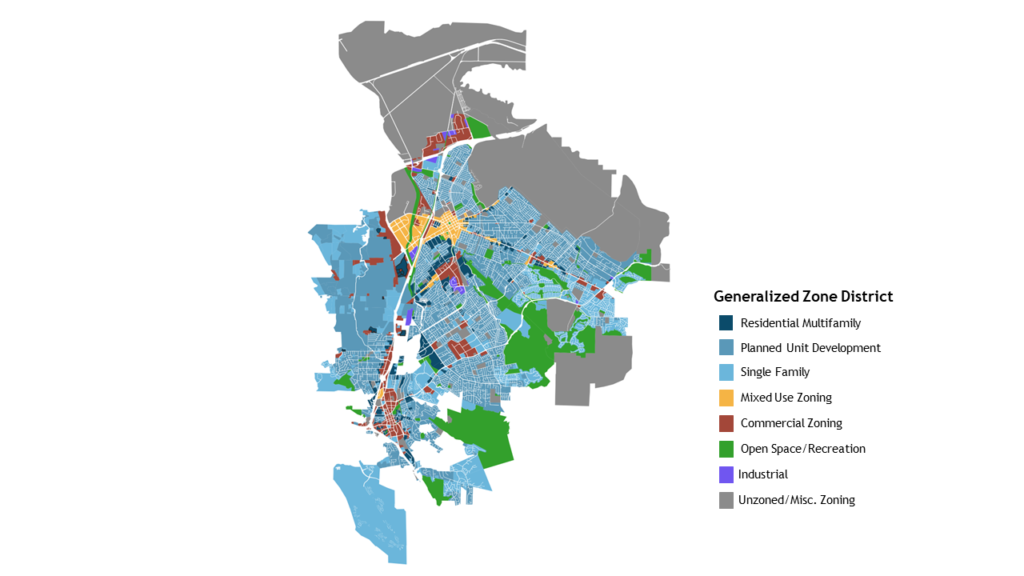

Without this, jurisdictions are competing for tax revenue. On one side, this leads to cities cutting deals with businesses in the short term, or land use policies to make retail easier. Additionally, you get land use decisions aimed at maximizing revenue for a jurisdiction rather than trying to balance housing, economic development, equity, and environmental needs. Here is an example from my hometown and the two adjoining cities.

These cities (Concord, Pleasant Hill, and Walnut Creek), serve primarily as bedroom communities for the major East Bay employment centers (Oakland, Livermore, etc.). Despite this, the amount of land zoned for commercial uses is the same as the amount of land zoned for multifamily and mixed use uses combined (5.7% in both cases)[3]. I would argue that this represents a concern by land use officials to conserve land for sales tax revenue rather than a considered approach to community.

Tax sharing would not wholly solve this problem – even in the Minneapolis case, the local jurisdiction keeps a significant share of the revenue – but I believe it would curb the worst behavior we currently see in regions.

Aligning Transportation Policy with Land Use/Housing Policy

Currently, there is a spatial mismatch between transportation planning and land use planning across commute sheds. Currently, transit and transportation policy for a region is set by the MPO with input from transit districts and local jurisdictions. Since the MPO controls federal transportation dollars, they are the agencies that decide on investments in how people move about the region. While I do believe that there is a need for more centralization and coordination amongst transit agencies in regions as well as federal funding for transit; I do believe that the mismatch between transit planning and land use planning can make transit systems less effective than they could be. For example, low density zoning in transit rich areas lowers the number of potential riders, creating unprofitable routes. Conversely, sprawl and dispersed activity centers can strain a transit system and make service unreliable as agencies struggle to serve riders who are far out.

Furthermore, the MPO already at the correct level to address the commute shed. Here is the Bay Area’s

By bringing together your land use authority and transit service planning under one agency, a region would be able to better align transit services and multimodal transit investments with land use decisions. This promises more non-automotive trips, reduced vehicle miles traveled, better functioning transit systems, and savings as routes are aligned with density.

Improved Services

Additionally, moving to a regional approach would allow for better services. One difficulty for small scale builders is that processes and regulations vary between jurisdictions. This would allow small scale builders to “scale up” without having to worry about differences in regulations. Additionally, having permitting authority and land use at this geographic level will allow for more resources to be put into customer service and advance planning.

Examples of this include IT systems for processing building and entitlement permits. Currently, jurisdictions often use legacy systems without robust features which make permitting efficient and paperless. While this has improved, there are often still backlogs as review staff are overloaded. Ideally a regional permitting office would be able to staff with greater efficiency and provide applicants more assurance to work within multiple jurisdictions.

Additionally, a regional level would provide planning resources to currently underserved communities. Currently, there is a large imbalance between jurisdictions on planning. Some jurisdictions have their planning needs met by their local COG, have part-time state help, or hire contract planners, while richer/larger jurisdictions have entire departments to provide long-range planning and implementation. In this way, communities with non-local staff often have plans and ordinances which are patchwork and poorly implemented. By moving planning to a regional level, planners involved in the planning could be linked into the implementation of the plan, providing follow through on investments and projects laid out in their planning work.

I want to acknowledge that without changes to streamline housing development, increased funding for transit, and forward-looking policies to address pressing issues like environmental justice, unequal investment, and car-centric development standards; moving to a regional planning organization model would not yield the results needed to address the pressing issues we face. However, a regional model offers us the best opportunity to provide positive outcomes. At a regional scale, planners can align with the labor and commuting patterns of residents, helping to better shape growth in sustainable ways. They also can offer improve services to underserved communities; and help provide balance when areas do not contribute their fair share. Finally, from the perspective of good governance, regionalization improves transparency by providing more eyes, improves efficiency by removing middle management and expensive contractors, and provides more capacity to implement community goals and priorities. In my next essay, I will provide a hypothetical of how this could be implemented, looking at the State of California.

[1] Chapple, Karen. 2014. Planning Sustainable Cities and Regions: Towards More Equitable Development. New York: Taylor & Francis.

[2] Minnesota House Research Department. 2020. Minnesota’s Fiscal Disparities Programs. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota House of Representatives. https://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/pubs/fiscaldis.pdf.

[3] Based on analysis by the author, using public data from those governments